QuIP IN ACTION:

Case Studies

BACKGROUND

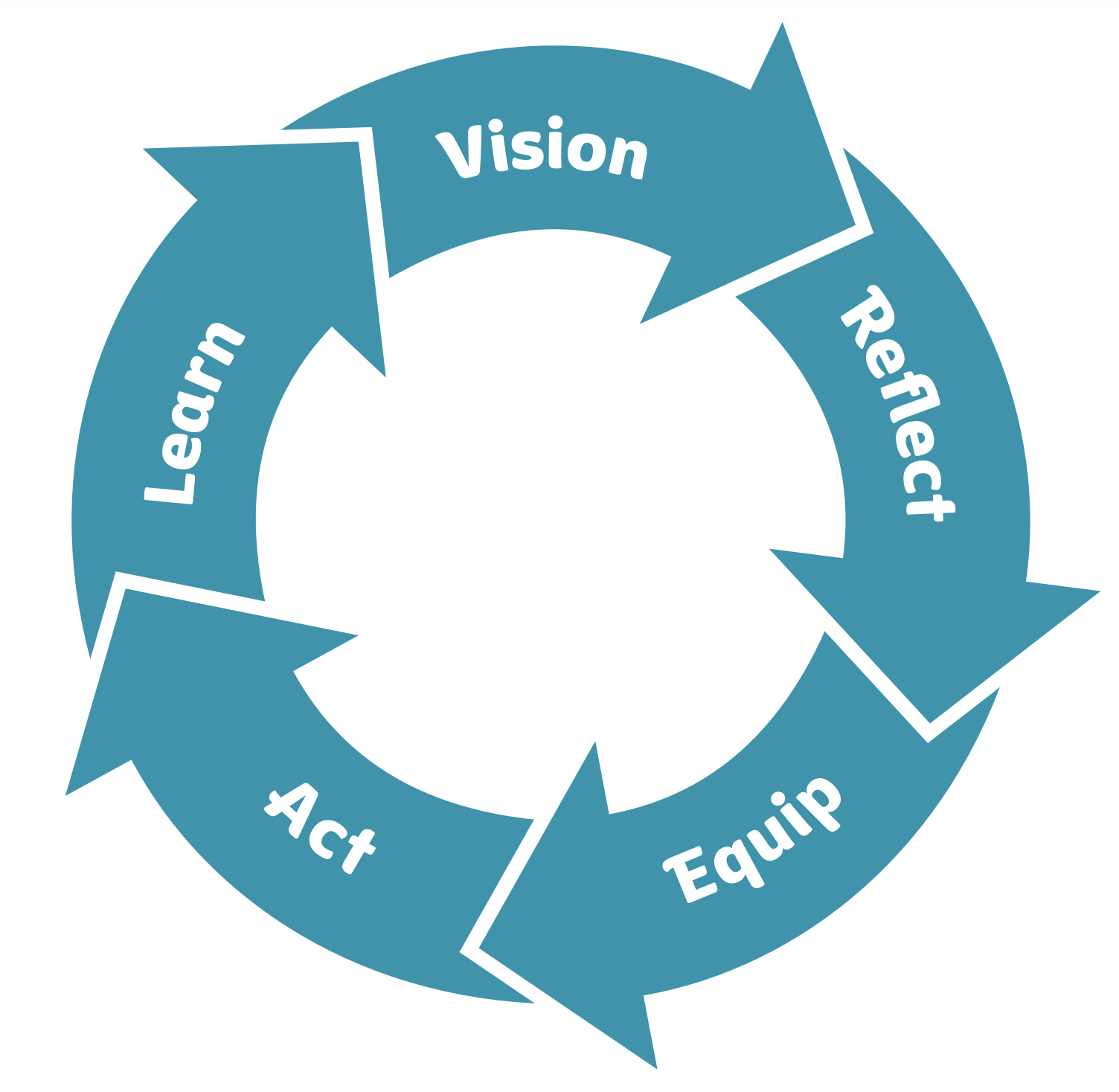

Tearfund is a Christian charity working in over 50 countries. They aim to tackle poverty by responding to disasters, advocacy work and community development. These evaluations explored the impacts of the Church and Community Transformation programme, known as CCT. Through partnering with churches, Tearfund aims to mobilise churches to take an active role in addressing community issues. The programme does not provide material support, rather assists churches to envision the change they want to create and provides facilitator training for members of the church, so that they can guide the process depicted on the right. Examples from communities working with partner churches include setting up skill-based training sessions, a blood bank, a litter-picking scheme and a savings group.

Tearfund believes that churches are well placed to foster change as they are often well respected in their community and may have access to useful resources. Their CCT programme aims to mobilise churches to identify the needs of individuals and the community, whether that is physical, spiritual, emotional, economic, environmental or social. To date, Tearfund has introduced church and community transformation processes in more than 40 countries, using QuIP to explore their impact in four of these countries.

To read Tearfund’s full 2022 overview report, see here.

WHY QUIP?

Tearfund chose to use the Qualitative Impact Protocol (QuIP) because of the exploratory and outcomes-based approach to collecting evidence of change. Where possible, the interviewer and interviewee know as little as possible about the intervention being explored and there are no direct questions about specific inputs or activities. Instead, participants are asked about any changes they have experienced in selected outcome domains (based on a theory of change), and what they perceive to be the reasons for any change (or why there hasn’t been any change). Avoiding direct prompting is designed to reduce confirmation bias; respondents only reference an intervention if they think it is linked to some significant change (positive or negative). The community-owned and more freeform nature of the CCT initiative and the lack of baseline or other monitoring data mean that it is challenging to measure the contribution of CCT using more experimental methods.

Tearfund is committed to learning about what works and what doesn’t directly from those affected by the programme. QuIP and the causal mapping used in analysis place the emphasis on reflecting respondents’ own perceptions of change and constantly linking back to the words used by respondents to keep the analysis process transparent and accountable.

THE APPROACH

In 2016, Tearfund commissioned Bath SDR to undertake a QuIP study in Uganda and this was followed by studies in Sierra Leone and Bolivia. In 2021, Tearfund conducted the final study of the series in Nepal themselves. The narrative data from these studies were coded separately and then merged into one file in the Causal Map app to analyse them together. Although the questionnaires, execution and results of the studies varied between countries, they shared the aim to explore whether the CCT project was achieving its aims in communities, and therefore focused on the following domains:

- Access to food

- Cash income

- Expenditure and assets

- Relationships (intra-household and within community)

- Faith

- Wellbeing

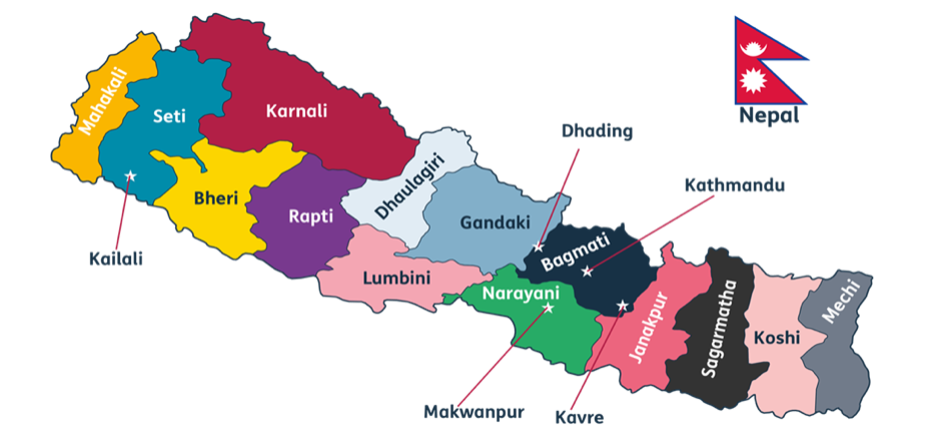

At least 4 locations were visited in each study, with approximately 12 respondents and two FGDs per community. The map highlights the areas visited in Nepal. Local Tearfund officers were involved in selection of communities based on characteristics which made them either ‘typical’ or ‘atypical’ cases of interest, including geography, caste, main religious communities in the area, and other relevant contextual factors.

QuIP does not require baseline data or comparison groups. Instead it gathers self-report data from respondents about what they believe are the reasons for change in their lives over a defined period, so QuIP evaluations usually focus resources on people who – it is assumed - are likely to have experienced some impact: only community members from areas where the project was active were interviewed. Researchers located a cross-section of respondents using snowballing techniques which usually started with some sort of community ranking exercise with key informants in the community. They attempted to split interviews equally between men and women, and respondents’ age brackets were also noted to aid comparison between gender and age groups. Where possible both individual interviews and focus group discussions were divided into men and women, and younger and older participants; this was designed to control for any differences in opinion or experience between these groups which may not otherwise have come out in individual interviews conducted in people’s homes.

FINDINGS

Data from these four studies allowed Tearfund to better understand which aspects of poverty the church can affect when they work with the community. Overall, the stories of change positively reflected the CCT process and broadly supported Tearfund’s theory of change. However, the research also highlighted the overriding impact of external challenges such as unpredictable social and economic crises which communities cannot always address alone. Unsurprisingly in the last study in Nepal, the Covid-19 pandemic was a negative driver of change in relation to wellbeing and finances.

Despite being affected by a range of negative factors such as unpredictable weather patterns, economic crashes and Covid-19, overall people reported positive changes in their lives. Analysis using Causal Map showed that even in challenging circumstances, CCT contributed to improvements in people’s lives including people’s self-worth, relationships and increased income. Analysis enabled Tearfund to track back from these outcomes to understand what drives changes in these and other key areas relating to the programme.

Tearfund’s theory of change is that CCT can increase hope in participants by improving relationships within a community, household and with faith. In all four studies participants reported an increase in hope and emotional resilience, defined as ‘the ability to respond to stressful or unexpected situations and crises' (see The Children’s Society, ‘What is emotional resilience?’ www.childrenssociety.org.uk’).

Respondents said that increased hope and confidence also had a positive effect on wellbeing and nearly three quarters of people interviewed reported their overall wellbeing had improved.

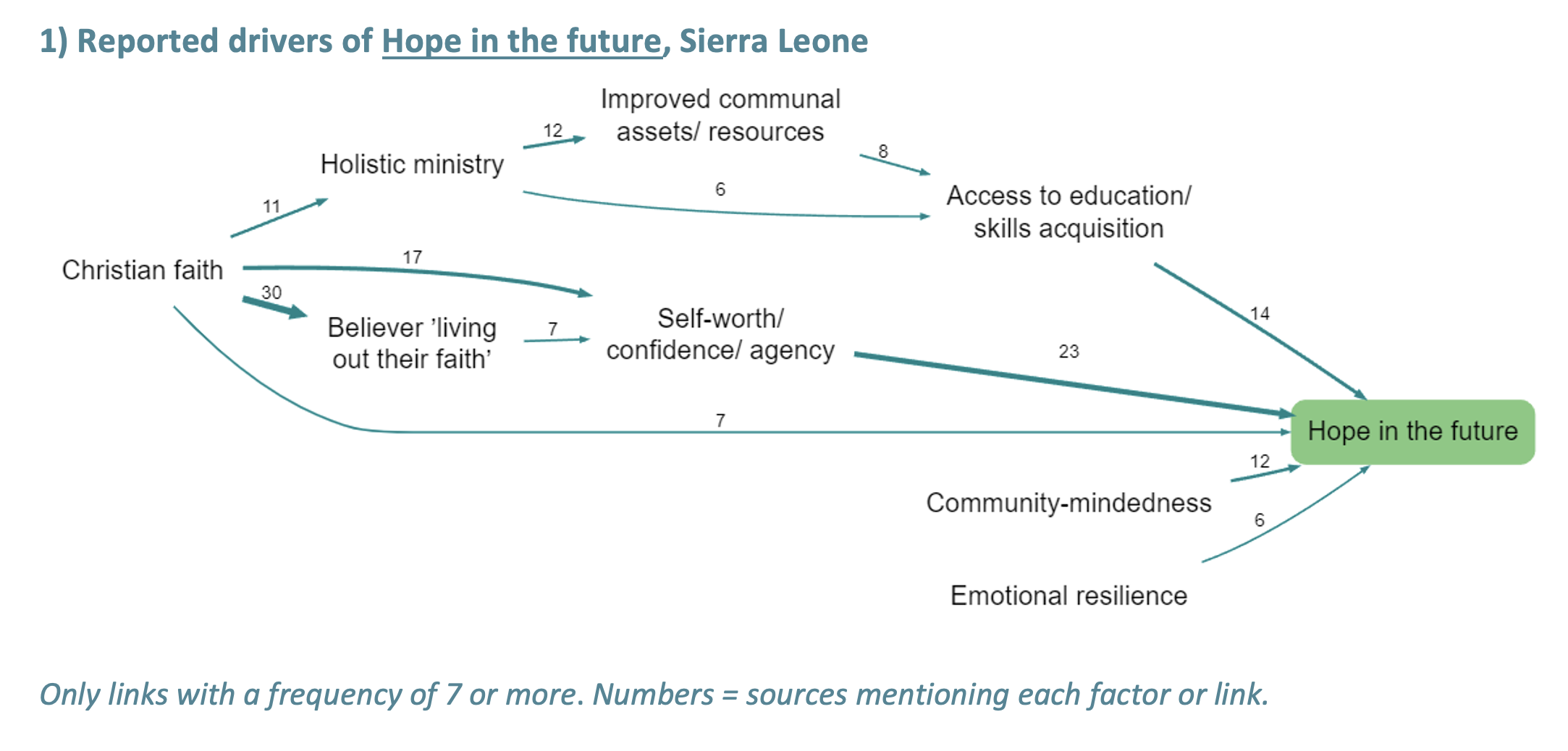

This first causal map shows what respondents said led to increased hope in the future in Sierra Leone. Christian faith led to increased self-worth or confidence which, alongside community mindedness and access to education/skills acquisition, led to hope in the future.

Increased hope had several influencing factors including

- Christian faith

- Improved community relations

- Improved access to education and skills training

- Increased self-worth, confidence and agency

Improved relationships within the household are a key intended outcome for the CCT process as respondents say they can contribute to improved wellbeing. Half of respondents said their relationships had improved over the last few years, and some of these stories can be traced back to CCT activities.

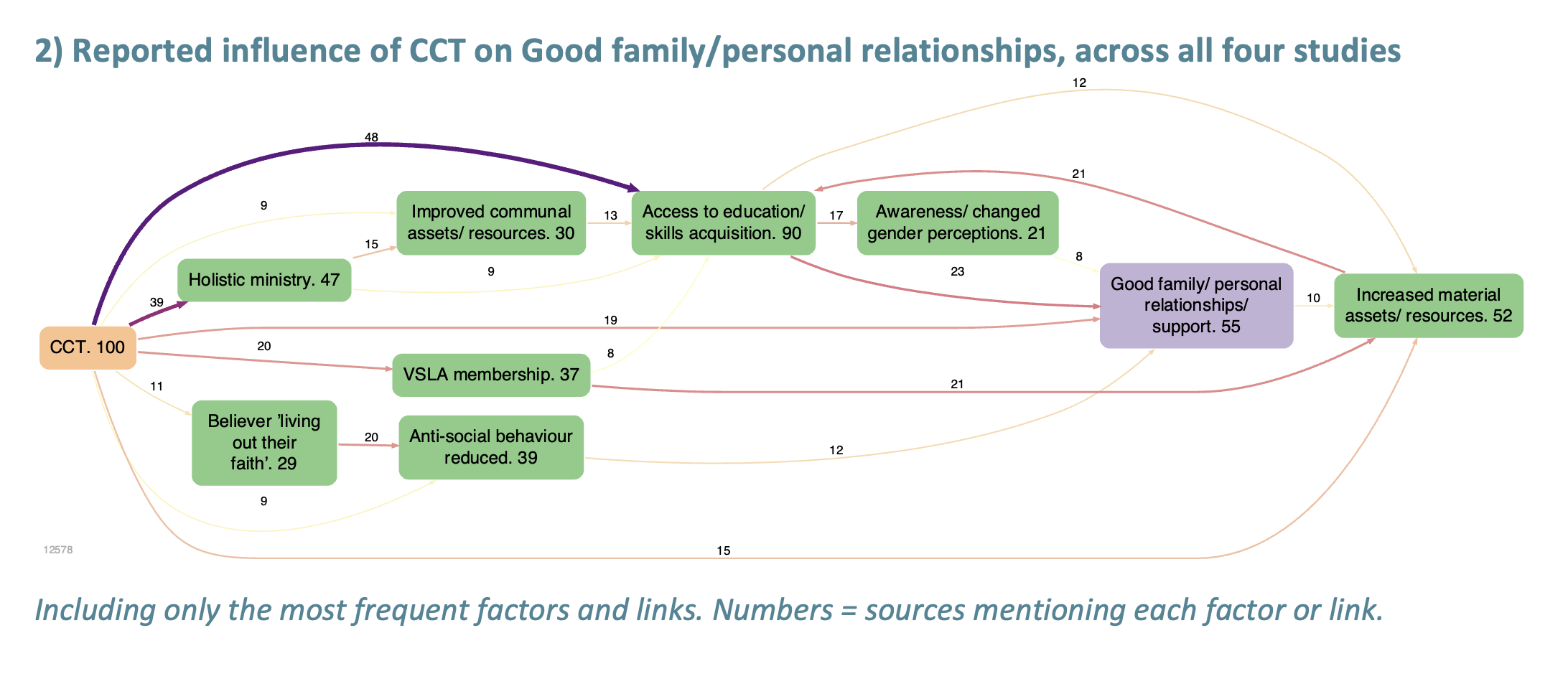

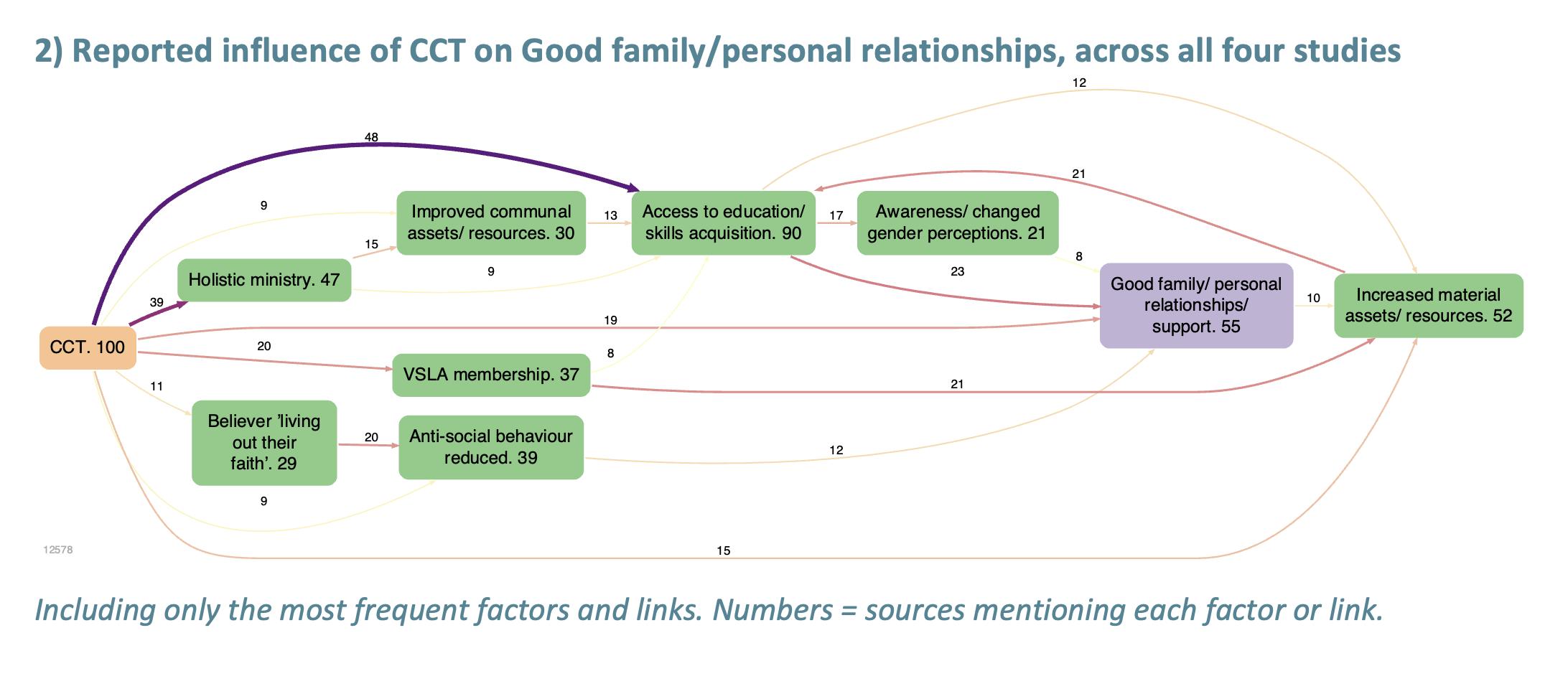

The map below shows that 19 respondents said that CCT led directly to improved family or personal relationships or support, but there are other paths which also lead indirectly.

The type of interventions which respondents engaged with varied in different places, but also often included bible study classes.

In Nepa ‘sangsangai’ - a family and community relationship education class - was reported to have improved family relationships.

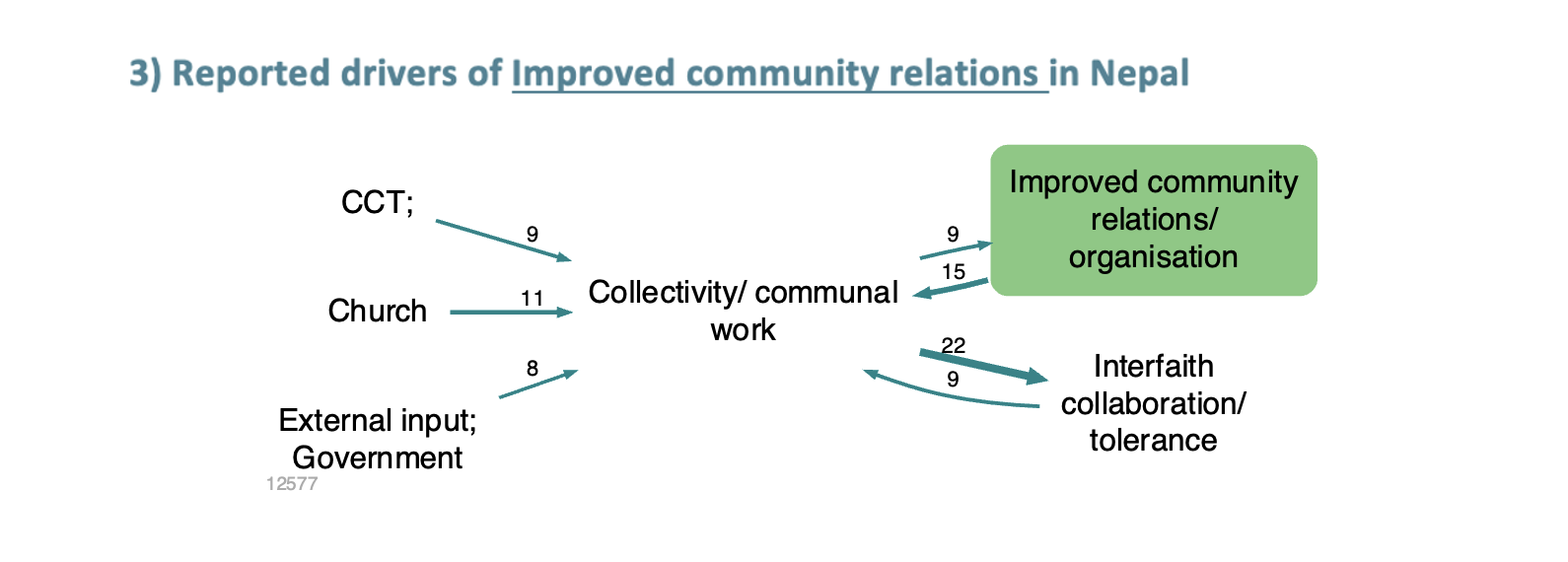

Improved community relationships were also reported, with reports of a range of positive impacts such as improved access to water, increased community assets and better conflict resolution.

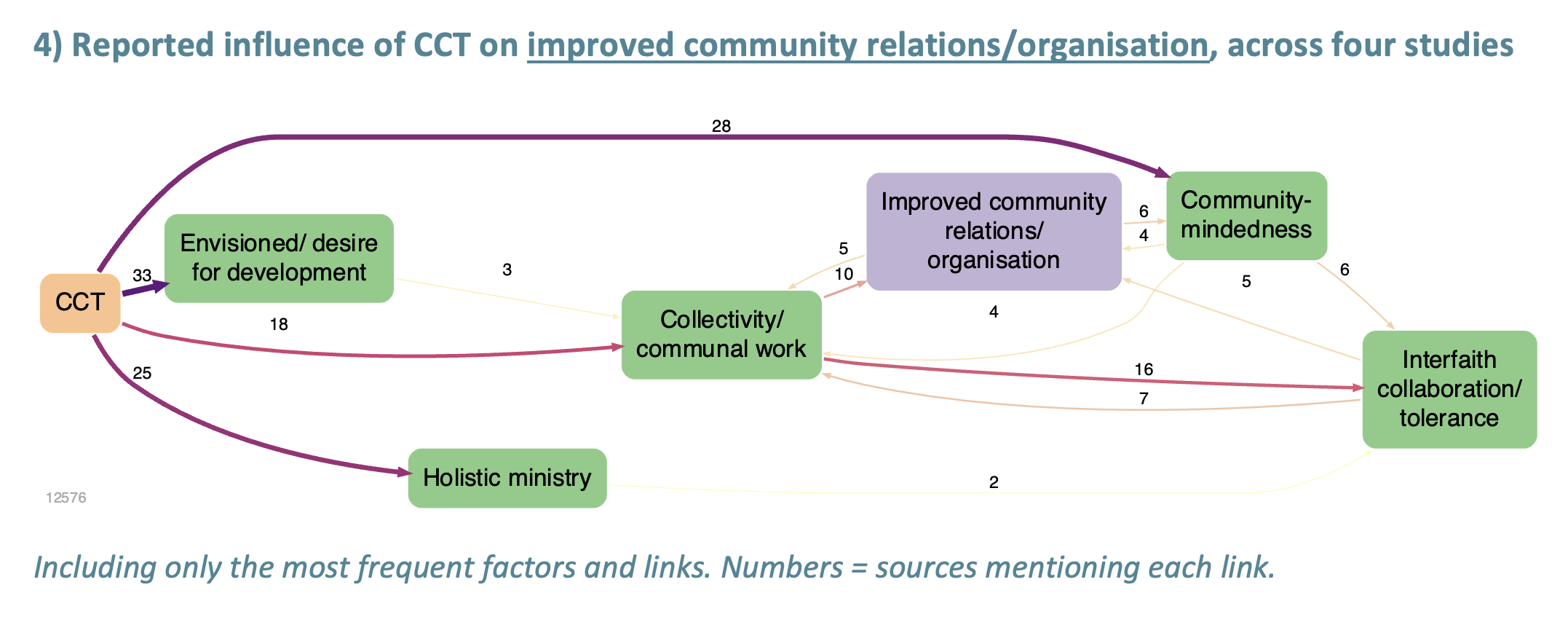

Across the studies, around a third of respondents said there had been an improvement in interfaith collaboration and tolerance in their communities.

Five of the main reasons given for this improvement were as result of CCT; working together, church witness, holistic ministry, inclusion and community-mindedness.

Map 4 also shows feedback loops between collective work on the one hand and improved community relations and interfaith collaboration on the other.

Interfaith collaboration/tolerance has a feedback loop as many respondents noted how working with other faiths encouraged tolerance and for some this facilitated continued and further collaboration.

This respondent shares how they saw working together with other faiths contribute to better interfaith relations.

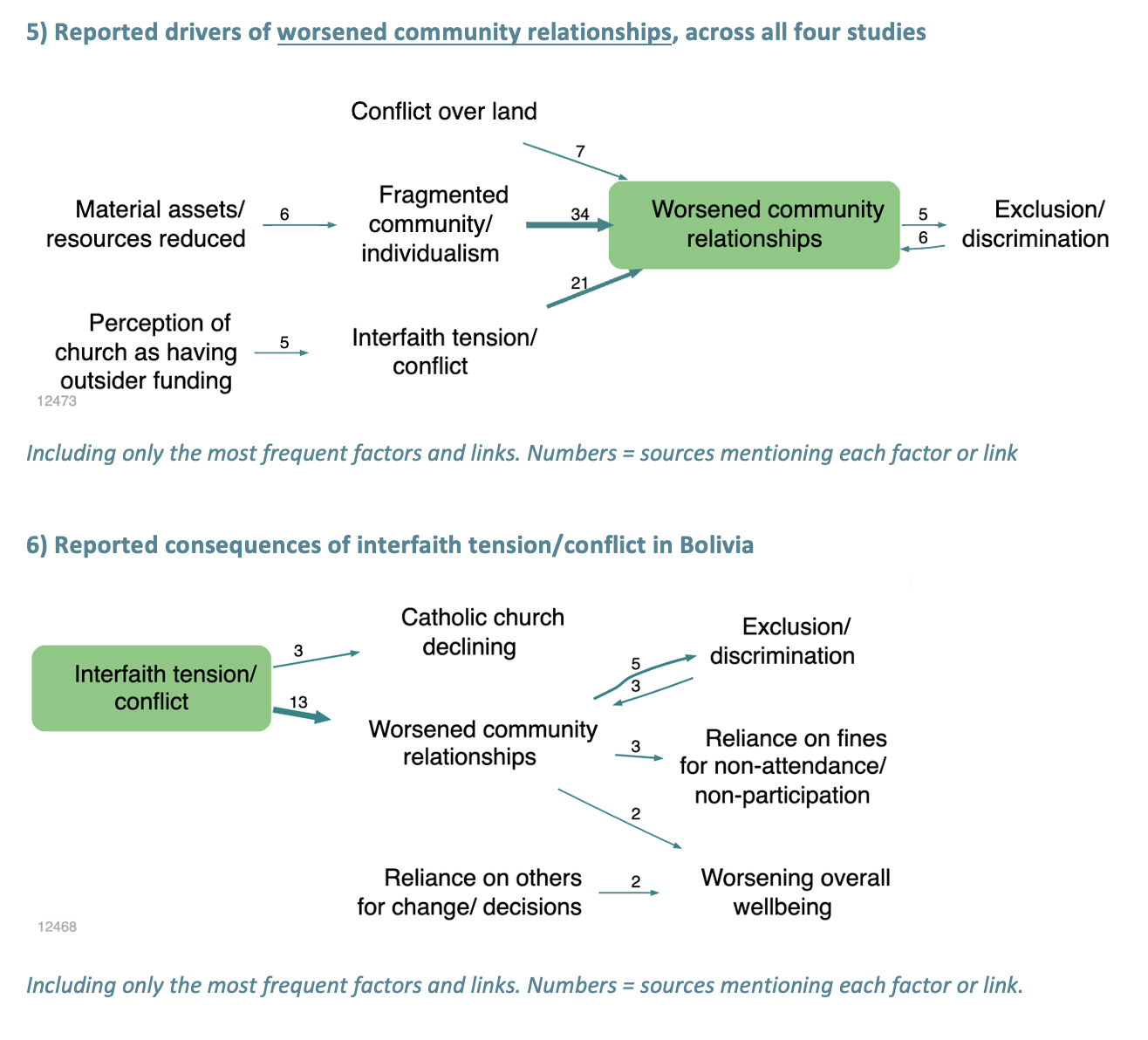

However, there were some negative stories of change concerning relationships, particularly in Bolivia where tensions within the community was the most cited negative change. This was often linked to conflict in community meetings over unequal access to communal assets such as water or schooling.

It was also a result of tension between evangelical Christian and Catholic communities regarding consuming alcohol at fiestas. As the map below shows interfaith tension and fragmented community/individualism were the largest reported influences of worsened community relationships.

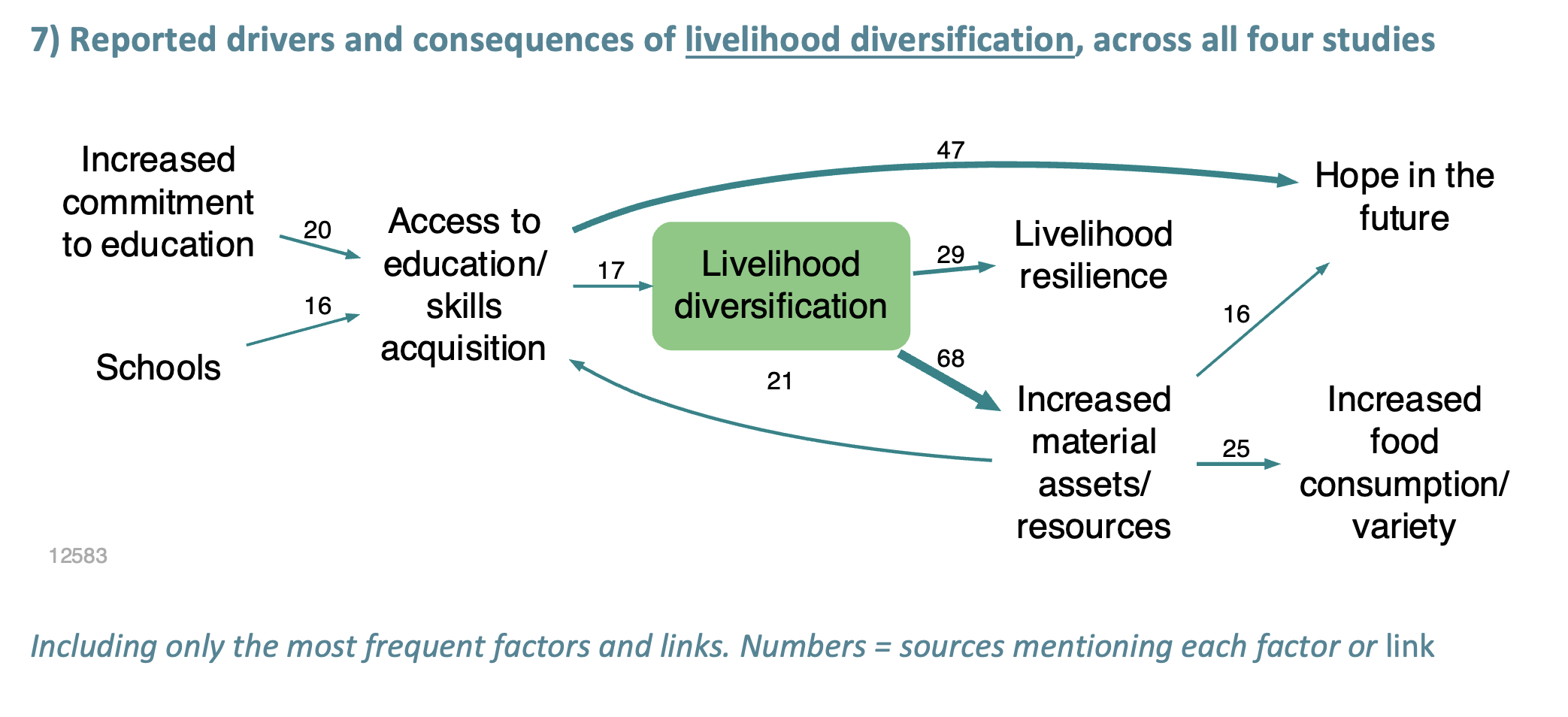

Tearfund believes that the CCT process will help communities learn to be more economically resilient and utilise the resources and abilities available to them. Resilient livelihoods are defined as ‘the capacity of all people across generations to sustain and improve their livelihood opportunities and wellbeing despite environmental, economic, social, and political disturbances.' (Measuring livelihood resilience: The Household Livelihood Resilience Approach (HLRA)’, World Development, vol 107 pp 245–263.) This evaluation found evidence that the CCT process did lead to more resilient livelihoods for some people; around 40% of respondents linked more stable livelihoods to their participation in the CCT process.

Membership to community saving groups reportedly helped participants to save money which led to them being more able to meet their households needs.

For some (around a quarter) their economic situation had stayed the same, a positive in the context of negative external challenges such as drought, unpredictable weather, economic crises and the Covid-19 pandemic. Some respondents also reported a decrease in financial stability due to these factors. There were also positive stories regarding purchasing power and income; 40% of people interviewed said that their income and purchasing power had increased.

As the map below shows, many people reported that increased access to new skills led to livelihood diversification. Respondents had started a range of new income generating activities such as rearing livestock, selling produce and planting cash crops. A few (13/96) respondents reported that climate change and unpredictable weather led to them stopping agricultural activities or planting crops that were more drought resistant like cassava. There were many stories of livelihood diversification leading to increased access to materials and resources and resilience.

CONCLUSION

This research has enabled Tearfund and their partners to better understand the contextual factors that are contributing to positive change in communities, while at the same time identifying factors that can undermine positive impacts. The experience of using a blindfolded, exploratory approach within these communities can be seen as disempowering and non-participatory, but Tearfund ensured that in each community the results were shared and discussed. They shared their experiences of using QuIP on the first evaluation study for the book Attributing Development Impact (2019), specifically on how they worked with their partners and the communities to ensure that they felt part of a learning process rather than being monitored or tested.

“At the start of the process they [local partners] were a bit unsure, but they really bought in by the end, and contributed a lot during the workshop. I think they were really pleased with how the study went, and really understood afterwards why we’d done it the way we did. We really want this kind of buy-in from our partners because we don’t want the learning to stay with us, we want it to be with them. It’s about our partners thinking about what they can learn from this research, what are they going to do differently.’’

On ‘unblindfolding’ and sensemaking...

“I visited each community, firstly to thank them for taking part in the research. Then the main thing was to share the findings and celebrate their success, reinforcing the message that ‘you have done this, not us.’ I told them we’d been a bit reticent about doing it in a way where we weren’t telling them who the research was for, because people might feel we were deceiving them, but we wanted people to feel completely free to tell us about their whole wellbeing. However, people were understanding. They said ‘yes, that makes sense, because this way we could be more honest with you’.

They really understood why we’d done the interviews blindfolded, so that was good. I facilitated mini workshops where we talked about the findings from QuIP and dug a little deeper. For example, sometimes participants had mentioned things we didn’t know about, like a small local NGO; and we wanted to verify those kinds of things. We got some really good stories which were helpful in understanding some of the results. People shed a bit more light on things that had come up in the interviews, and it was nice to go deeper where we were unsure of some of the results. Going back to the communities and doing the unblindfolding was great. We’ll definitely be doing that again.”